In Full...

I talked a little bit about my thoughts on AI Personal Assistants previously. I find the idea very exciting! My general sense is that they are more complex to implement than people first imagine, but will be brilliant for relatively simple tasks that don’t involve a high degree of personal preference. What I didn’t explore in that article is the effect of their successful widespread adoption.

AI as a Personal Assistant

The interaction model suggested for these personal assistants is fairly straightforward: you say “Get me a taxi there” or “Bring me a pizza here” and any AI Assistant worth its salt will be able to translate your request into a series of necessary actions and negotiate with whichever third-party services are required to achieve the desired outcome.

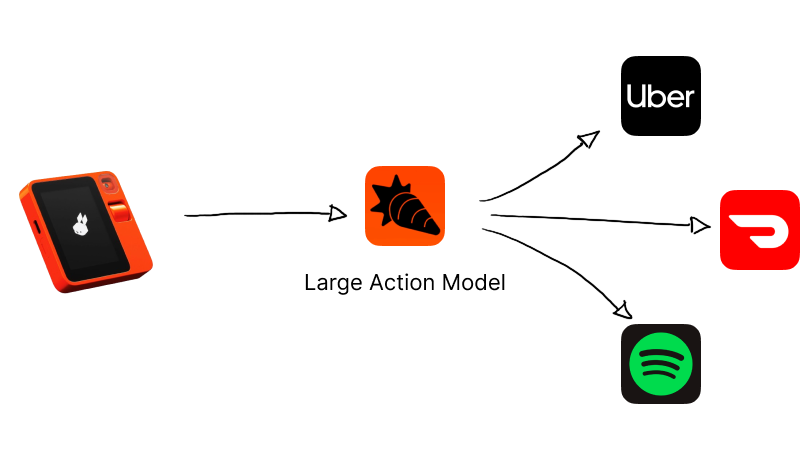

If we ask an AI assistant to book a taxi, the AI itself will then interact with another service, whether via an API or (as the rabbit r1 does) directly interacting with websites and apps on your behalf, parsing the result and then feeding that back to you in the form of your conversation.

For the rabbit r1, that means connecting your existing services to the platform. If you want your AI to be able to book a taxi then you will need to connect your Uber account first. The same with DoorDash for a pizza or Spotify for music.

That appears to be a perfectly sensible approach. We hand over control of our other accounts so that we can let our assistants use them on our behalf, as we might a human assistant. Now, instead of tapping on a screen, we’ll just speak or type and get exactly what we want from the connected apps.

Under the above model, we’re applying an existing and accepted paradigm to the new technology. In this case, we’re replicating what a human would do; open an app and get a result. The perceived benefit is in our own interaction – or lack thereof – with the end service.

From Stratechery:

When it comes to designing products, a pattern you see repeatedly is copying what came before, poorly, and only later creating something native to the medium.

It feels like this is what is happening here. Connecting the AI to an app is just a copy of what came before. So, what is the native approach that is only possible as a result of the new technology?

Well, the huge benefit of an AI is not that it can simply replicate human functionality as a human assistant would, it’s that it can blend that with the more “traditional” functionality of computers that humans are not necessarily good at.

One of those things is doing multiple things, at the same time, very quickly.

Aggregators and the Status Quo

It won’t surprise you to learn that very few services on the internet are truly benevolent gifts to society. Wikipedia perhaps. Archive.org, maybe.

Most websites are balancing their own motivation to make money with the quality of the service that they provide to users. Google is great, but the days of 10 blue links are long gone – the results for any mildly competitive search term are headed with at least a screen of ads. Price comparison sites like Booking.com appear to exist to make customers’ lives easier but their revenue comes from the supply side, typically in the form of referral fees or ads.

Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory defines how these businesses work and the framework that they operate under. The internet is full of examples of companies that have, by securing both sides of a market, built incredibly successful businesses. One of his primary examples of an aggregator is Uber.

The initial technical idea behind Uber (“a taxi at the tap of a button, with live tracking on a map and easy payment”) was a good one! At launch, it was also relatively difficult to replicate. But not impossibly hard. Uber knew this; technology was not a moat on which it could rely. To build a real moat, they needed to invest in aggregating both sides of the market:

Supply (Driver Network): Uber spent a lot of money rapidly building an extensive driver network to serve its app, ensuring there were always drivers available. They did this initially by paying very well, with high fees on journeys, bonuses and referral rewards.

Demand (Passengers): Uber aggressively invested in marketing and branding to build its customer base, especially in building referral networks (at one point I had hundreds of pounds of credit on the app, just from these referrals). Uber’s prices when they launched were also ridiculously low. When Uber launched in London, a journey in an Uber Black Mercedes S-Class (the only Uber that was available) was cheaper than a Black Cab.

Uber spent billions of dollars executing all of these strategies and through its aggregation of the supply of taxis and passengers in a given locale, “won” many major cities. But that win came at a huge cost, subsidised by investors. Eventually, it had to normalise costs; driver pay went down and passenger costs went up. The moat that they’d built was wide and deep, but competitor services popped up and built their own networks by offering similar incentives as Uber had.

The key element for Uber though is that it still has the most users, who return to the app because it still has the most available taxi drivers, who in turn return to the app because it has a consistent supply of customers.

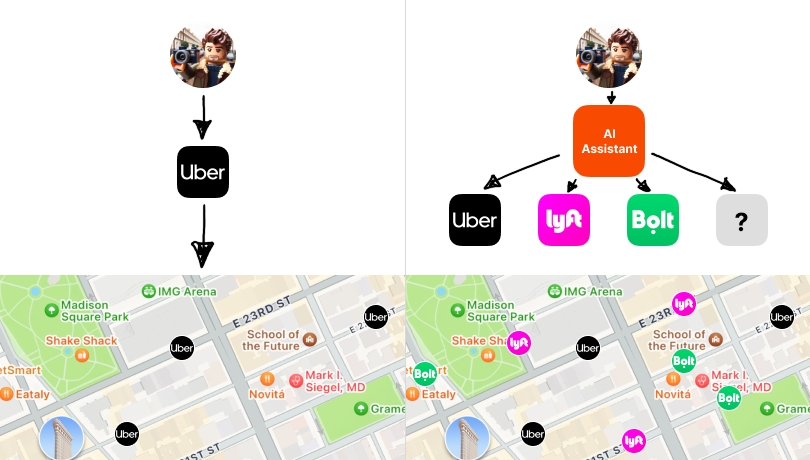

The actual service that Uber offers though is not highly differentiated. In any given major metropolitan area, there are at least 4 or 5 significant apps that provide the same service – routing a Toyota Prius to the customer to take them where they want to go – at around the same price point. Ultimately their product is a commodity, with little differentiation from other competitive apps. They, to some extent, rely on customers’ (a) habitual use of their app and (b) lack of motivation to check every service at once for the best price/arrival time.

What happens though if we introduce an intermediary into the equation which is motivated to check every service for the best deal? Say, an AI which can do multiple things, at the same time, very quickly?

AI as a Personal Aggregator

This is the big paradigm shift: introducing the Personal Aggregator. Instead of a human user using one platform to look for a taxi, why would AI not look at all of the platforms to find the best match?

Of course, this doesn’t apply just to taxis. A sufficiently powerful AI will be able to rely not just on the results of booking.com, Amazon (not technically an aggregator) or DoorDash, but the entire internet.

The fundamental shift here is in the motivation of AI itself. An AI Assistant is likely part of the user’s personal infrastructure – not that of a third party motivated by the desire to make profit. Of course, there is an assumption here, but I think it’s a fair one. The early generalised intelligence that we’re seeing produced by the likes of OpenAI isn’t focussed on doing just one task well, it does everything, from history homework and language translation to coding and eventually price comparison across the internet.

With a motivation of always returning to the user the best possible deal for a given stay, product or other service – without concern for who the seller is - and having looked at the entire market, an AI assistant stands to be the ultimate aggregator.

As part of our personal infrastructure, the motivation of the AI will be to go wherever it needs to to get the right deal, using whatever blend of requirements that the user has provided it with along with the historical preferences that it has learnt about you. For our taxi example, one person’s personal aggregator may aim for the cheapest possible car at the cost of comfort and expediency. The same AI acting as a personal aggregator for someone else might prioritise comfort over cost and so on.

The fundamentals of how we intertact with a huge array of businesses could completely shift, not just because using the AI is easier, but also because it is the best way to secure the best deal. The widespread adoption of this type of interaction with an AI as personal aggregator could have massive consequences for all sorts of businesses, and not just the existing aggregators.

If we go beyond the creation of an increasingly competitive (but arguably more efficient) market, the intermediating effect of the AI will disrupt one of the core tenets of Aggregator Theory: that of the direct relationship with the end user. When that direct relationship is removed in favour of the ease of use and better user experience of the AI, it is not just the transaction that is being intermediated, nor the buying decision, it is also the pre-buying decision. What is the point in marketing a commodity product from Store X to buyers if they’re going to buy it via their AI?

It may feel that we’re a while off this reality, but as Bill Gates said “We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten”.

The effects on the markets that these commodity products exist within will be drastic, but there will be an increased incentive for differentiation to occur.

Embracing the New Paradigm

The advent of AI as a personal aggregator heralds a transformative era in how we interact with and perceive the digital marketplace. This shift isn’t just about convenience or efficiency; it’s about a fundamental change in the power dynamics between service providers, aggregators, and consumers. AI won’t necessarily be great at telling us what to buy, but it will be at telling us where to.

For decades, aggregators have thrived by simplifying choice and monopolising user attention. They’ve dictated market terms, often at the expense of both service providers and consumers. However, as AI steps in as the ultimate intermediary, it will potentially democratise access to the market. By evaluating all available options to identify the best deal, AI will disrupt the traditional aggregator model, shifting the focus back to the quality and value of the service itself.

This change will compel service providers to innovate and differentiate. Yes, initially there may be a race to the bottom in terms of price but differentiation will need to occur instead as a result of focusing on enhancing quality and user experience.

Moreover, the rise of AI assistants as personal aggregators raises important questions about the future of marketing and customer relationships. As AI becomes the gatekeeper of consumer choices, traditional marketing strategies might lose their efficacy. Businesses will need to adapt by finding new ways to engage with both AI systems and their users, focusing more on the intrinsic value of their offerings rather than just visibility and brand recognition.

The emergence of AI as a personal aggregator is not just a technological advancement; it is potentially a catalyst for a more equitable and consumer-centric marketplace. It will challenge existing business models and forces a rethink of market strategies across various sectors. We’re not there quite yet, but we are standing on the brink of a paradigm shift and it is essential for businesses to understand and adapt to these changing dynamics. The future promises an era where choice is not just about availability, but about relevance and quality, in which consumers are hopefully empowered by AI like never before.>